In October, St John, in Clerkenwell, east London, will be 20 years old. In itself, this should not be an extraordinary thing. Two decades: it's hardly a lifetime. But restaurant years, like dog years, are different. The capital has a handful of longstanding dining institutions: bustling Sweetings, in the City; Rules, purveyor of game in Covent Garden; Wiltons, where one may eat oysters in Mayfair, assuming one has first remortgaged one's home. Pretty much everywhere else is in constant flux, joints opening and closing, chefs arriving and leaving, the crowd descending and then, ever-fickle, moving on: an exhausting and sometimes heartbreaking spin cycle of briefly modish ingredients, cuisines and cooks.

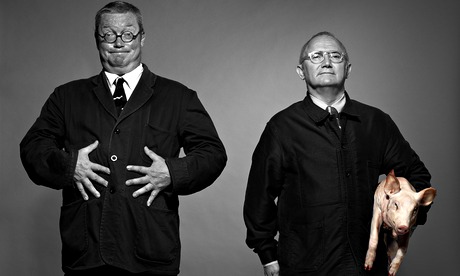

How, then, to explain St John's long, happy and singular life? Its proprietors, Fergus Henderson, formerly its chef, and Trevor Gulliver, his business partner, are damned if they know. "We just quietly go about our business," says Gulliver, coffee slopping over the side of his cup as he slaps the table. "We don't do vision." Henderson contemplatively sips his mid-morning madeira. "Yes, and there's still lots to do," he says. "There's always tweaking to be done." Better to list the things they don't believe in than those they do. Set menus? Not even when business is bad. Posh wines from around the world? France will suffice. Bawling out the staff? Not necessary. The lure of MasterChef? No, thanks. Finally, they come up with a word: rigour. "There is a rigour here," says Gulliver. "You have to be quite stubborn to do something like this."

St John, whose most famous dish will always be a plate of roasted marrow bones served with toast and some bouncy parsley, happened, they insist, with relatively little planning. Henderson, who trained as an architect, was cooking with his future wife Margot at the French House Dining Room. He wanted somewhere bigger – the French House was the size of a pocket square – but he needed a backer. "Our Cupid was John the olive oil man," he says, nodding in the direction of Gulliver. Had they met before? "No!" Was it love at first sight? "Definitely not. There was some fencing and some finding out to be done." Gulliver had enjoyed a hit with that most noisy of watering holes, the Fire Station in Waterloo, with the result that his idea of a restaurant involved sofas and booming music. Henderson, on the other hand, wanted bentwood chairs and a soundtrack of diners' conversations. Thanks to a third partner, Jon Spiteri, manager of the French House now head maître d' at the Holborn Dining Room, Henderson won.

It was Gulliver who found the building, a former smokehouse close to Smithfield Market; the last smoking having taken place in 1967, it had since been used as a place to grow bean sprouts, a squat and the HQ of Marxism Today. The space made no sense at all – long and narrow, not to mention relatively difficult to spot from the street – but they took it on anyway. "Clerkenwell was like one of those post-apocalypse films in those days," says Henderson. "The designers and architects had yet to arrive." He longed to put in a bright blue rubber floor, but the budget didn't allow it. The walls were whitewashed for similar reasons, though the decision to hang no art would have stood even if he and Gulliver had been as rich as Croesus. There were to be no distractions. The food would take centre stage.

And what food. Henderson's menu was wild, outlandish, spectacular (spectacularly awful, the more faint-hearted would say): pig's ears with sorrel and chicory, blood cakes with fried eggs, tripe and onion, those notorious bones. No seared salmon, no chicken, no crowd-pleasing side orders. This was resolute, timeless cooking: good, seasonal and served with a certain amount of solemnity by helpful people in long, white aprons. It was puritan, but it was generous, too. It was Florence White by way of bourgeois France. Naturally, the result was a scarily empty dining room – at least at first.

"There was a recession on," says Gulliver. "We were naive about that. For the first two years, the bar was empty." Slowly, though, the restaurant began to fill. The reviews worked like magic. For Fay Maschler (Evening Standard), Jonathan Meades (the Times) and John Lanchester (the Observer), it was love at first sight. Ditto AA Gill (the Sunday Times), who once told me Henderson's cooking could move him to tears. The art crowd came (Sarah Lucas, Angus Fairhurst, Tracey Emin), and so did Bryan Ferry, Cate Blanchett and Madonna (this was during her tweed phase). It was, too, a haunt of the editor of the Daily Mail, Paul Dacre – which tells you quite a lot about its particular appeal. St John was now a destination, and the source of some fascination. When squirrel appeared on the menu, the newspapers were full of it. When the Sun got wind of one its starters, a plate of raw carrots and a boiled egg served with aïoli, it ran a page lead along the lines of: "£4.95 for this? You've got to be joking."

In 1998 Henderson was diagnosed with Parkinson's. Ultimately, his illness would chase him from the kitchen. But still the cogs of St John turned. In 1999, he published his classic Nose to Tail Eating, in which he attempted to charm cooks into working with the bits of the animal they might previously have avoided. ("The flesh from a pig's head is flavoursome and tender," he writes in a favourite passage of mine. "Consider, its cheeks have had just the right amount of exercise … and the nozzle has the lipsticking quality of being not quite flesh nor quite fat, the perfect foil to the crunch of the crispy ear.") First editions now sell for hundreds of pounds. In 2003, a second branch of the restaurant was opened, St John Bread and Wine in Spitalfields. In 2011, there was a foray into the hotel business – the St John Hotel in Chinatown won a Michelin star for its restaurant then went into administration in 2013 – but Henderson and Gulliver have bounced back with a new cafe in Druid Street, Southwark, which sells their bakery's noted eccles cakes and excellent doughnuts.

Twenty years, and still fashionable, still beloved. Some of us can no more imagine London without St John than we can picture it minus Tower Bridge or St Paul's. "Well, restaurants shouldn't be about moments," says Henderson. "No, we leave it to other places to be popular," says Gulliver. "Which they often are. For a while." Beside us, the bar clatters reassuringly. The staff lunch is about to be served. It looks delicious. All is as it should be.

But St John isn't only an institution. It's also the most influential restaurant in Britain. After we finish talking, Henderson and Gulliver's assistant, Kitty, hands me a family tree: a list of names I've been nagging them to compile for weeks. It runs to several pages, is punctuated with loopy stories ("came to St John straight off the plane, sat at table 13 on his own, ate everything on the menu and then came to the pass to ask for a job …") and makes for happy reading. For on these sheets is written the story of the changing landscape of food culture over the last 15 years. Henderson's alumni are behind some of the best restaurants in Europe and America. My eye runs down the list, London first. The Anchor & Hope, the Modern Pantry, Hereford Road, Lyle's, Lardo, Trullo … crikey. Every corner of the capital is covered..

Talk to these graduates, quiet evangelists for duck's hearts and lamb's brains, and over and over you'll hear the same story: St John changed my life. "I can't think of another restaurant that has had such a seismic impact on the way people eat out," says Karl Goward, now the chef at Bistro Union in Clapham. "There are little blisters of it everywhere." Goward arrived at St John in 1997. "It was the only place I wanted to work," he says. "I wanted to eat that food, and I wanted to cook it. I was working in Battersea then, and when we finished on Saturday nights, I would get into my friend's 2CV and drive over there just to look at the menu. Other menus were so flowery: a cordon of this, an envelope of that. St John's was dark and bold."

He loved the kitchen immediately. "We'd all come from kitchens that were run with a rod of iron and you were barked at and berated. And those kitchens were full of people who didn't really like food. Fergus wasn't like that. He wanted us to eat and drink when we finished; he wanted us to learn. There were no recipes, no set routines. You either got it, or you didn't. We were prepared to follow him." And what he taught Goward stuck. "Fergus never diluted his ideas, and that was hugely impressive to us. When we meet up, we always ask ourselves: are we on the cutting edge? And I think we're all pretty happy that we're not. We have the courage of our convictions, something that's very different."

Ten years ago, Goward went to New York with Fergus to cook a week of St John dinners at Soho House – the restaurant's fame had been spread in the city by two of its most ardent American fans, Anthony Bourdain and Mario Batali – and it was thanks to this experience that, in 2005, Goward finally left St John, eventually taking up a job at Prune in the East Village. He opened Bistro Union in 2012. How often is St John in his mind now? "Every day. It's there in how I word the menu, it's there in how I put something on the plate. Tonight, we've got some beautiful Kentish carrots. We'll serve them with cow's curd and a bit of chopped tarragon. That'll be enough. They're really good carrots." Also on his menu: lamb's liver. According to Goward, the Clapham-ites really love it.

Jon Spiteri, Henderson and Gulliver's first manager and original partner, left St John after a couple of years, a decision he came to regret – though he has since become London's most distinctive and well loved maître d' (he helped relaunch Quo Vadis in 2012). For him, St John was about the staff as much as the food. "We had five rules," he says. "No music, no art, no garnishes, no flowers, no service charge. Thanks to that, we always had really good staff. We gave them the service charge, and they really worked for us. They were part of the family. And there was no standing up in a corner for 10 minutes for your break. They got a proper staff meal. We respected them." Why does he think the restaurant has lasted? "It's about sticking with the same thing and not trying to make huge amounts of money by being greedy. It's basically about generosity."

Spiteri was succeeded by Thomas Blythe, who recently helped Angela Hartnett to open the Merchants Tavern in Shoreditch (he is now a consultant to Tonkotsu). Blythe is full of stories: the time the restaurant's metal shutters wouldn't roll down, and he had to spend the night inside, keeping guard; the time a mariachi band burst into the rammed bar and began playing, much to Fergus's disgust. Blythe had started as a pastry chef – his job interview involved drinking a bicicletta [white wine and campari] with Henderson – but when he heard Spiteri was off, he set his heart on stepping into his shoes. "I remember this French guy came in wearing concierge trousers and a tie, and they didn't give him the job because he was wearing loafers, and Fergus doesn't approve of shoes that don't have laces. So I threw my hat into the ring." For him, St John was all about Fergus. "His menu briefings were legendary. We'd all gather round the pass, and then he'd … embellish. There was a dish of pigeon with pease pudding and spring onion. So he'd say the bird was resting its head on a pillow of pease pudding with a spring onion for a harp. When it was squirrel with shallots he'd talk about recreating the bosky woods. It was florid and visual. Some of the waiters felt a bit self-conscious but I didn't. I just used to go out into the dining room, and repeat what the man had said. The people at your table would laugh, but they'd order it." Converting diners, that was what he loved. They'd come in looking a bit nervous, and they'd leave happy, well fed and ready to spread the word. He stayed for 15 years.

Dan Lepard, baker extraordinaire, was there right at the beginning. Among other things, he remembers Margot Henderson (who now co-owns Rochelle Canteen in Shoreditch) helping out in the kitchen with her new baby on her back. "I think she suggested that we put chicken and salmon on the menu – things you could actually sell," he says. "But Fergus said 'no'. That was what he did. He said 'no' to things." Lepard only stayed for a few months, but he has never shaken off the restaurant's ethos. "It was about eliminating stuff, sending a dish right back to its beginnings. I remember this bowl of really good new potatoes. They were going to be served with butter and parsley. Fergus didn't want the parsley. Then he didn't want the butter. It was a case of: you want an apple, or you don't want an apple?"

Harvey Cabaniss now runs Verde & Co, a magnificent deli in Spitalfields. He worked at the French House, and then at St John. He agrees with Lepard. "The approach was like Coco Chanel's: take one thing off before leaving the house. It was all about the produce." To him, St John seemed more civilised than any kitchen on earth. "Radio 4 was on all the time, and there was always the most wonderful staff lunch, and there we'd be, making brawn …" Why has it endured? "Because Fergus is there every day, watching it, and he doesn't ever try to reinvent the wheel. I ate there three weeks ago, and it was as beautiful as ever."

For a few days, I follow the trail. The facts and figures, the myths and the stories, pile up. Can it really be true that in the early days, St John was so cold, diners – in truth, there were only two – had no choice but to eat in their overcoats? That there was every possibility that its first tablecloths could have been old sheets from Jon Spiteri's parents' Tunbridge Wells guest house? (These precious relics had, you see, already done sterling service in the French House.) That its chef de partie now turns out 5,000 Welsh rarebits every year? That Fergus and Margot were once caught … Ah. Here I shall draw a discreet veil. But while I can't always get to the truth on many matters, on certain subjects there is universal agreement. Everyone tells me about Fergus's humility, his refusal to water down his ideas, his talent for mentoring. And I must say that it's lovely, listening to so much praise. The restaurant world is not known for its miniature egos, or for loyalty.

Then I go home, and look at Kitty's notes again. What an octopus! I could go on for ever. St John has formed empire builders (Theodore Kyriakou, who went on to open the Real Greek), and waiters (Botti Vaughan, now at Pastis in New York); butchers (Paul Hughes, who helped to set up the Ginger Pig) and bakers (like Justin Gellatly, whose Bread Ahead does such booming business in Borough Market). On her list are big, glamorous restaurants, and tiny local places in old shops with only 10 tables (though thankfully more of the latter than the former). Six couples have married. One former employee, Nino Mancari, now cooking in Delaware, has a tattoo of the St John logo on his left arm (it's perched beside an inking of Alice Waters of Chez Panisse, who once cooked a special dinner for Henderson in her restaurant using only his recipes). Two former kitchen porters have since gone back to Lima to open their own St John-inspired bakery. It is all rather amazing. It has taken two decades, but almost without our noticing it, a kind of revolution has taken place. The choice these people – these disciples – have given us, and the goodness. It lifts the heart. I pick up the phone. I need to book a table.